John Bass, Associate Professor, School of Architecture + Landscape Architecture (SALA)

When John Bass joined UBC’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture in 2002, he was no stranger to the politics of contested landscapes. Since the late ‘90s, Bass had worked in the Delta region of California’s Central Valley on a series of projects that posed ways of reconciling environmental and economic interests. The work allowed him to explore how graphic methods of documentation, analysis, synthesis, and representation he had acquired in his architectural training could describe conflict and reconcile contentious interests. It also set the stage for the next 18 years at UBC, wherein Bass has worked—and continues to work – in the arena of collaborative, Indigenous, community-based research.

In 2006, Bass became involved in his first Indigenous community collaboration—a large, SSHRC-funded project called the Coastal Communities Project, which partnered with six colonial and Indigenous communities on the BC coast. During this time Bass began to see potential in applying his skill set to support justice for Indigenous community partners. “As I started to work in Indigenous contexts, it was clear that my allegiances were with those communities. Whatever I was going to do was not going to be simply to express conflict between colonial Canada and Indigenous groups; it was to look for things that would be potentially useful, whether legally, economically or simply historically.”

A few years later, Bass was on a boat ride off the coast of Vancouver Island with an Elder from one of the Central Coast Indigenous community partners. “Our host points over his shoulder and says, ‘See that mountain over there? Well, that’s where they put our reserve. And you see the mouth of that river? That's where we had our fishing camp. They didn't give us the fishing camp site. They gave us the side of the mountain, which was useless.’” The anecdote sparked a research idea and together with his research assistant Bass embarked on a self-funded project that—in part--mapped the traditional villages of the Nation and compared those sites to land formally reserved beginning in the late 1800’s. “We identified two pieces of land that should have been reserved—at the mouths of rivers, where the land met the sea--but were instead displaced to the sides of adjacent mountains, land that was not part of the food gathering practices of the people.” The analysis also mapped many sites that were not considered in the two days’ work that the Indian Reserve Commission spent on the issue. Eventually part of a larger project to mark territory and ancestral houses, the research was presented to the Hereditary Chief and community cultural society in 2014.

Bass also points to a 2006-2010 collaboration with an Indigenous community on northern Vancouver Island, where he was called on to reconstruct the legacy of a Hudson’s Bay Company fort that was built in 1849 and ultimately became the basis of the community’s permanent village there. “We assembled a collection of photographs, maps, and surveys, and from them created a graphic timeline of the physical evolution of the village, beginning with the construction of the fort, to the village that gradually replaced it. We demonstrated that there were questionable pre-emptions--the conversion of public to private property, crown land to private land—completed after the [Douglas] treaties were signed by the Band.” The resulting work, which Bass assembled into a report with maps, images and diagrams, became a part of a legal case for repatriation of the land and was used in the local school curriculum.

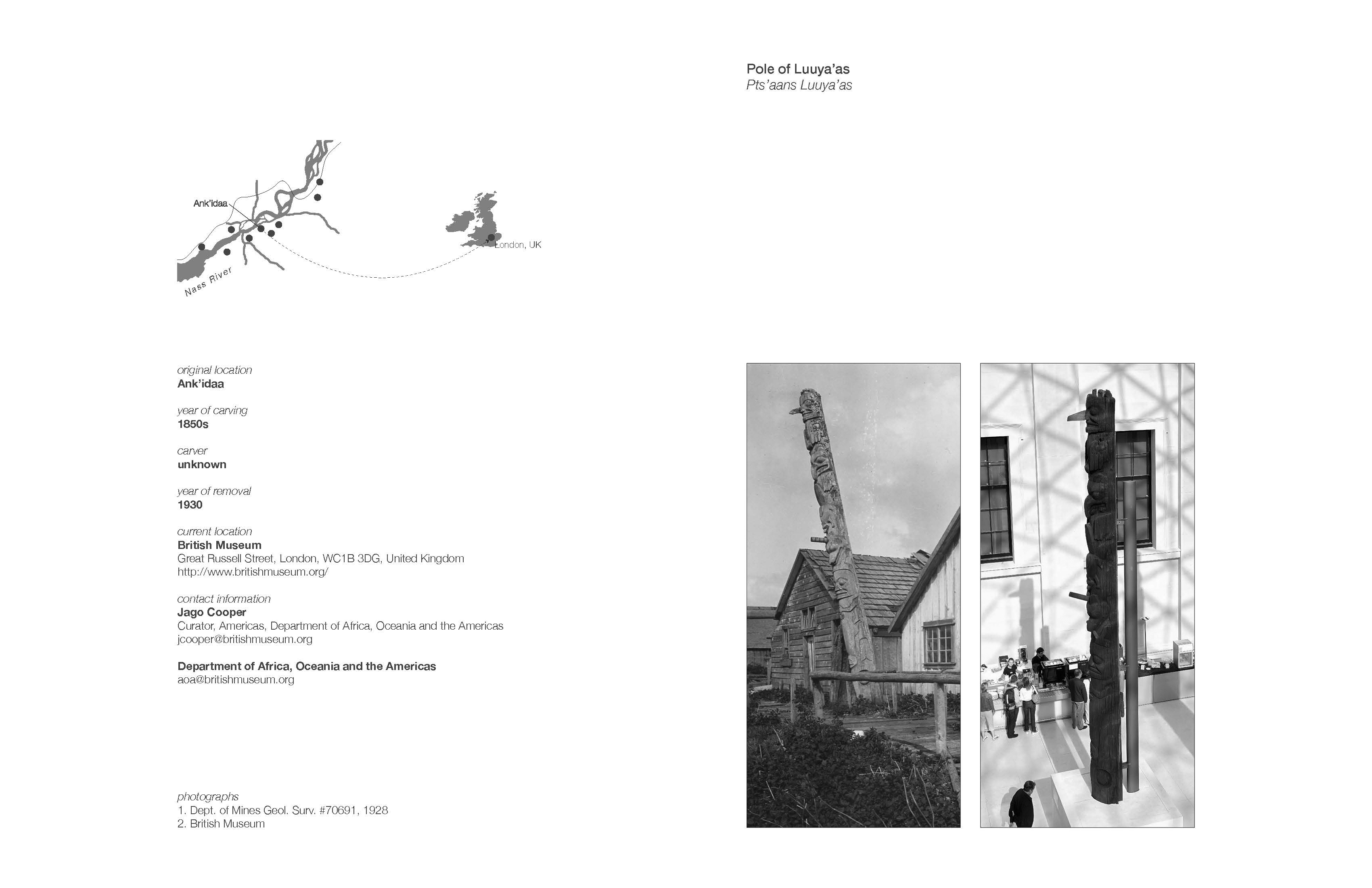

Another project that allowed Bass to support reconciliation through research and design was the Displaced Poles Project, a collaboration with Nisga’a Nation that took place in 2013-2014. The idea for the project was inspired by the suggestion by a Nisga’a Elder that a community space Bass had designed would be a “good place to put that pole that we just recarved that’s over in that museum in London.” The project involved locating all of the poles that had been taken out of the Nass Valley in the early 20th century and that now reside in European and North American museums. Bass organized the collection in a document that identifies the past and present location of each pole and includes contact information for the appropriate curators at their respective museums, should the Nation wish to pursue repatriation of the poles.

Bass thinks of his work as project-, rather than research-based, which in practice allows him to more easily adjust to the needs and knowledge of his community partners. The downside is that his more fluid approach often falls outside the parameters set by funding institutions, which in turn made it difficult for Bass to support his earlier work through mainstream sources. “A lot of the work falls between the disciplinary cracks of ‘is this research? Is this architecture? Social sciences? What is this?’”

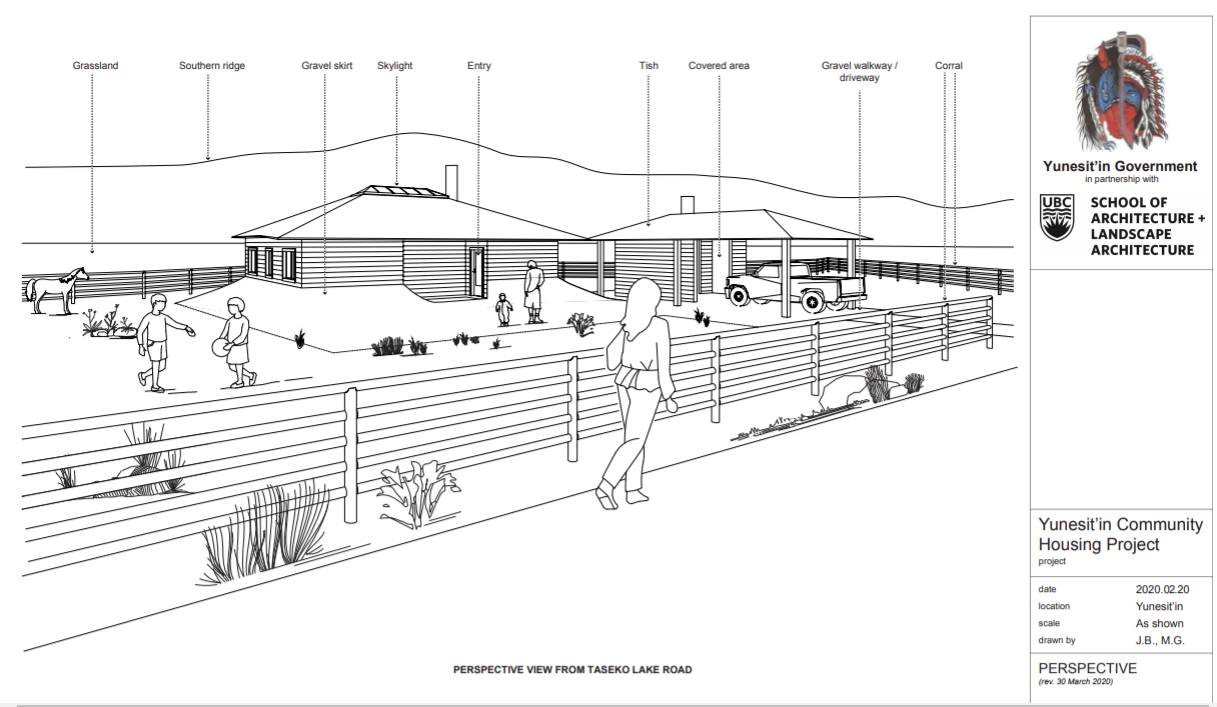

His more recent work has taken a more conventional tack however and, perhaps as a result, Bass has successfully received two grants—the Community-University Engagement Support (CUES) fund and an IC-IMPACTS grant from the Canada-India Research Centre of Excellence—to support his current research collaboration. Working with Yuneŝit'in, one of the Tŝilhqot'in Nation’s six communities, Bass and his project collaborators will co-design a house prototype. The Wildfire House Project aims for a housing design that is culturally appropriate, affordable enough to be replicated, and that mitigates the health problems associated with the inferior indoor air quality often found in on-reserve housing and exacerbated by climate-change induced wildfires.

Before the Yuneŝit'in housing project, Bass collaborated with another community, the Heiltsuk Nation of Bella Bella, which was then and continues to face a housing crisis. When the Heiltsuk Nation approached UBC for research support, the community estimated a need for 150 mold remediations, 160 home renovations, 100 new homes and 120 new lots to support community demand over the next 10 years. Guided by a Project Charter co-developed by the Indigenous Research Support Initiative (IRSI), the Heiltsuk Tiny Homes Project is a multi-year collaboration with numerous UBC and private partners that resulted in the design of a sustainable and community-endorsed tiny house, the first set of which are now nearing completion. Bass’s contribution, in the early stages of the collaboration, was to co-supervise a graduate architecture student’s creation of housing designs based on an extensive community engagement process.

Over the past 15 years Bass has learned some "hard lessons". "In my very first encounter in a First Nations community, I went in to a meeting with a preconceived idea, and I said 'you should do this and this and this'. After I got done talking, the [community representative] told the lead P.I. in the project that he would be happy if he never saw me again. That was like, ouch really? I didn't think I was so bad. But then I realized, you need to slow down; understand you don't know it all." Bass absorbed this and other lessons, ultimately becoming a trusted and sought out research collaborator who has earned the respect of both UBC and Indigenous community partners. As to advice he might give young researchers who are new to Indigenous community engagement, he emphasizes the need to be patient, open, and flexible, to consider community need first, and—above all—to listen.

Note to the reader: Communities featured in this story were contacted for their permission to include information pertaining or belonging to them. Any community names and images contained in the story reflect those communities that responded, providing their permissions by the time that this article was published. We will update the story if and when additional permissions are received.

Listen to John Bass describe his approach and advice in his own words: